This is a random observation while listening to some on a pair of good headphones:

We like to in hindsight attribute the success of disruptive products to practicality when in truth these products succeeded because they elicited some previously-impossible emotional experience in their user.

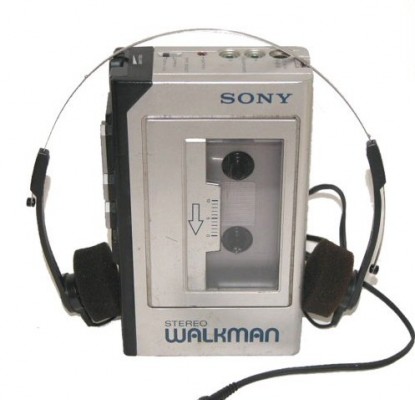

Here’s the crux of the epiphany: When I was eight I got one of the very first Sony Walkman’s (this is the closest pic I could find but I swear mine was even more old school). I had a bunch of teeth pulled right when this miraculous device debuted and my parents figured it would a good distraction to fill my head with music during the recovery period. This turned out to be a genius move on their part and worked really well. In spite of having awful pain from every corner of my mouth, this new incredible way to experience music trumped everything and transported me beyond the pain. Now here’s why this is relevant:

Here’s the crux of the epiphany: When I was eight I got one of the very first Sony Walkman’s (this is the closest pic I could find but I swear mine was even more old school). I had a bunch of teeth pulled right when this miraculous device debuted and my parents figured it would a good distraction to fill my head with music during the recovery period. This turned out to be a genius move on their part and worked really well. In spite of having awful pain from every corner of my mouth, this new incredible way to experience music trumped everything and transported me beyond the pain. Now here’s why this is relevant:

Clayton Christensen (and by proxy many others) have cited the Sony Walkman in their explanations of disruption usually saying something to this effect: “The Walkman achieved disruption because it enabled young people to listen to music out of earshot of their parents for the first time.” This is a functional/practical motivation (ie. listening privacy, facilitated quiet rebellion) and while it may partially account for its success, I would submit that there was a more fundamental emotional-based motivation: “it enabled for the first time the undeniably cool & irreproducible experience to have music originate from between one’s ears.” This is akin to experiencing dry ice, static electricity or pop rocks for the first time- it’s just freakin’ cool!

No doubt practical motivations overtake the cool factor at some point and most disruptive products with any longevity can’t subsist indefinitely on coolness alone. But in the vast majority of past product success analysis from today’s vantage point, the coolness factor gets way undervalued. The ubiquity of white earbuds now makes it difficult for us to imagine thirty years back to a time when experiencing music that originated between your ears instead of from external speakers was as untangible as anti-matter & black holes are to us today.

Anyways, there’s no call-to-action here other than to observe that our “coolness bar” is perpetually raised higher each year and it’s impossible to see those case study products via the same lens of wonderment we would have had at the time they presented. I don’t dispute Christensen’s ideas on disruption re: underserved markets, competing against non-consumption, etc. but I think we need as entrepreneurs to acknowledge the role of a more parsimonious “I just gotta have the music inside my head!” motivation in explaining the success of a product like the Walkman.

No doubt when Apple someday develops the ability to deliver any smell on demand via the appstore, we’ll all run out and purchase an iSniff because “I gotta have any smell on demand!” And years afterwards the business historians will all concoct elaborate theories about the runaway success of this product explaining how we were economically-motivated and seeking to reduce trips to flower stores.

Both of the quoted insights are inaccurate: “The Walkman achieved disruption because it enabled young people to listen to music out of earshot of their parents for the first time.” and “it enabled for the first time the undeniably cool & irreproducible experience to have music originate from between one’s ears.” Neither is true. Headphones address both of these requirements, not the Walkman itself, and headphones have been around since the 30s (stereo headphones since the late 50s).

The Walkman's appeal was about the combination of portability and emotional attachment to music. Steve Jobs got the emotional attachment to music aspect right – it's about being able to access a vast range of emotional experiences from your (at the time of Walkman launch, bulky and difficult to manage) personal music collection anywhere and at any time – see his iPod product launches.

Ed, obviously headphones existed prior to portable music players. No argument from me that your comment is accurate in theory but in practice the Walkman was the first time en masse younger people could experience music this way (stereo's were hundreds while Walkman's were about $70). The point of my post is that _practical_ reasons are typically the ones that get cited in case studies after the fact but the true driving factors for adoption at the time are more sensory/emotional in nature. As you pointed out w/ the iPhone, it wasn't so much that practicality of being able to access one's music collection from anywhere that was compelling as much as it was cool to be able to choose from any of your tunes while out on a run.

Wrong x2. Little transistor radios in the 1950s were "cool" for kids, and they had earbuds of a sort, so they were portable, cool and had music originating between your ears. And, they were disruptive long before the Walkman. Regardless, that isn't the reason your parents bought one for you. To understand disruption, you need to look at the motivation of the buyer, and that wasn't you, or any other 8 year old. When I was 8, a different set of products was cool, but for the most part, non-disruptive. If the pattern isn't repeatable, it isn't a useful pattern or model to use as the basis for prediction, and it isn't a very good theory either. Predicting market success is the point of disruption theory, so your analysis is fatality flawed because it doesn't explain or predict anything, even if It was accurate.

Paul, thanks for the kind words. I realize you found my 5mo-old blog post and baited me so you could get SEO juice for your eBook giveaway. I'll bite and gift you the SEO b/c your response is off in two fundamental ways:

a) You're assuming I set out to prove something or propose a predictive model with this post. I merely made the observation that analysts like yourself like to retrofit explanations for disruptive trends with _practical/functional_ motivators while neglecting the more parsimonious "cool factors." I guarantee you could come up with some theory explaining the hole in the toy market that the slinky filled but the fact is, it was just a novel toy that just went viral. The point is while I'm sure you and other people have come up with great predictive heuristics for discovering markets ripe for disruption and predicting disruptive potential of certain products, this idea of explaining the viral adoption of toys through a purely logical/practical lens is misguided and mistakenly attributes the cause of it's spread.

b) "that isn't the reason your parents bought one for you" – really? What was the reason Paul? I'm pretty confident the cool factor is precisely the reason my parents (and many other parents) bought us toys like the Walkman. Sure some toys had educational value, social connective value, etc but a portable music player back in the day that gave us an experience we had never had was pretty clearly a gift exclusively for it's cool factor.

anyways, I never claimed my post held a repeatable, predictive theory. This is my personal blog and I post occasional thoughts to air out ideas publicly. I'm glad you've invented something more useful than a rambling it took me all of 15min to write up. It's lame that you're promoting your book by instigating and link baiting bloggers on old posts but hey whatever, sounds like you need the link more than I do. cheers